Czech engineer Marek Foltis builds a ten-cylinder two-stroke Jawa!

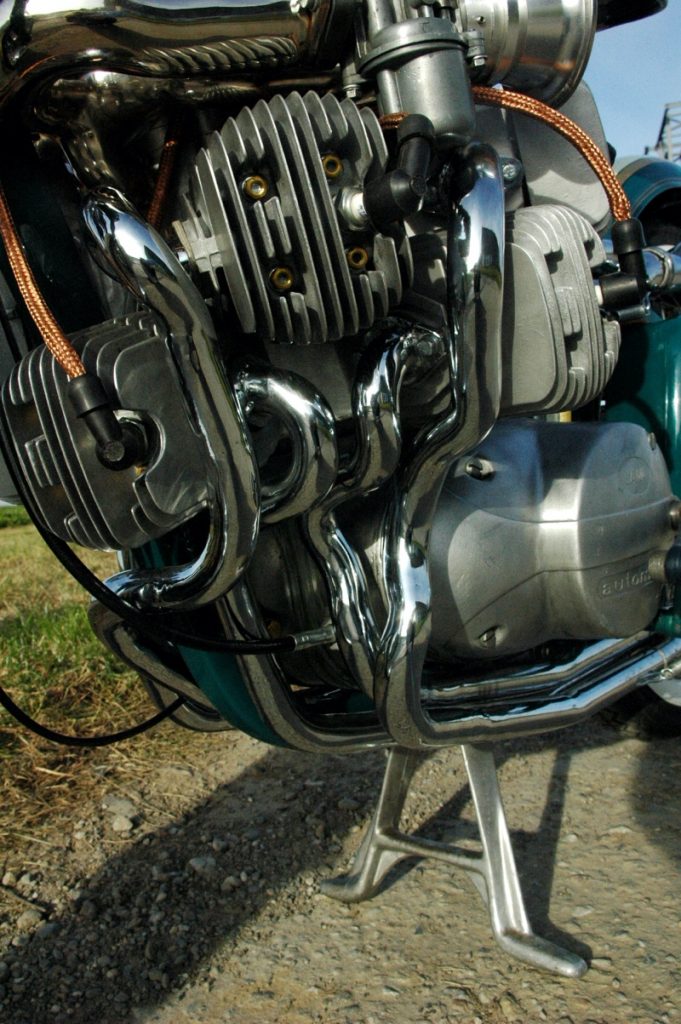

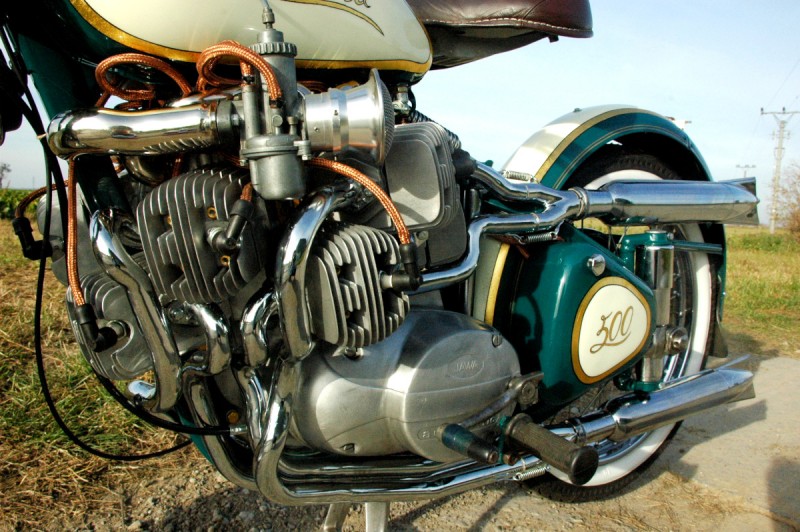

There are bikes that make you drool, bikes that race your blood, and bikes that simply blow your mind. For us, the “Bistella 500” is a true mind-blower — a supercharged ten-cylinder radial engine two-stroke built by our new friend Marek Foltis of the Czech Republic.

Marek started his motorcycle career at the age of 13 on a Jawa 21 moped before progressing to dirt bikes and motocross. Back then, he says, Jawas were really the only bikes available on the Czech used market, as the former Soviet nation had no history of bikes imported from the West:

“This created really strong subculture around Jawa and many enthusiasts kept Jawas even when much better Western bikes came up on the Czech market. It is an adventure to go on Jawa anywhere, because you never know what will break and you have to able to solve problem to continue your ride. I grew up in this environment, so I know every screw on Jawa bikes — when I close my eyes, I can see all the parts and their dimensions, so it was much easier to design the Bistella 500 engine using only Jawa engine parts.”

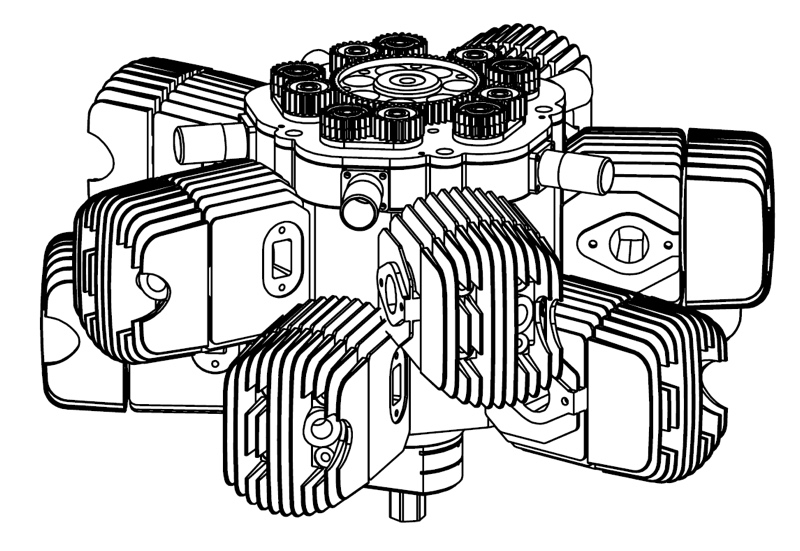

In fact, Marek used ten 50cc cylinders from a Jawa 21 moped just like his first one to create his 500cc radial engine — full circle! His inspiration for the layout was Pyscho Engine’s “Naga Lima” build, a twin-ringed radial engine that helps give the bike its name:

“Bistella means ‘twin star’ in Latin. In most of the world’s languages, the radial engine is referred to as a ‘Star engine’ — same as in the Czech language (my native language). I used double-row radial engine design, so it means two stars, so Bi – Stella…. and 500 is the displacement of engine: 500 ccm.”

He started with the oldest Jawa he could afford, a 1953 Jawa 250 Type 11 Perak — a bike he chose largely for regulatory reasons unique to the Czech Republic:

“When you want to legalize a custom bike in CZ, you have to pass multiple safety inspections. And our law sets baselines for safety based on the safety standards of the year when the base motorcycle was produced. So, an older bike means a lower baseline. So I chose the oldest Jawa available in my price range.”

What’s more, Czech regulation only allow one major part of the motorcycle to be customized. Obviously, Marek chose the engine, but that meant he had to leave the suspension and brakes alone! As you might imagine, that makes the Bistella 500 quite a handful on the road:

“It’s a life-threatening experience. It accelerates faster than it brakes. But it’s fun…you have to pay attention all the time, otherwise you could end up in a ditch after opening throttle.”

We reckon there are worse ways to go than at the helm of a ten-cylinder supercharged two-stroke! Marek says a lot of people tried to dissuade him from the project, calling him crazy or telling him there was logical reason behind it, but he’s glad he persevered:

“I don’t have talent for sports or art, but I can build engines, so I build them. That’s my domain of art. I can’t help myself. Can’t wait to be finished with Bistella because I have another engine already seizing my mind.”

Below, we talk to the man himself for the full story on this incredible machine!

Bistella 500: Builder Interview

• Please tell us a bit about yourself, your history with motorcycles, and your workshop.

I’m an engineer and quiet garage freak. 😀 I started riding motorcycles when I was 13 years old. First on a Jawa 21 moped (which is the donor for the cylinders, slave rods, and many other parts in Bistella 500).

After a while, I became attracted to dirt bikes, so I bought an old used dirt bike and started racing on local events. But then I finished high school and started university and I was not able to make enough money and have enough time to continue racing, so I sold my dirt bike and started restoring vintage bikes. I have restored multiple Jawas from the 60s, but the one I’m most proud of is a Motobecane MB1 1924 belt-driven motorcycle, which won me multiple Elegance awards. Then I swapped it for Jawa 250 Perak, which is donor for the Bistella 500.

• What’s the make, model, and year of the donor bike?

Jawa 250 Type 11 “Perak,” 1953.

The only bikes available back in the day when I started riding were old Jawas from the 60s and 70s, because we are an ex-Soviet country, so no used western bikes were available. So we had to ride Jawas only. But Jawa bikes are really unreliable, so if you want to ride it, you have to fix it all the time.

After a while you just know every piece of bike. This created really strong subculture around Jawa and many enthusiasts kept Jawas even when much better western bikes came up on the Czech market. It is an adventure to go on Jawa anywhere, because you never know what will break and you have to able to solve problem to continue your ride. I grew up in this environment, so I know every screw on Jawa bikes — when I close my eyes, I can see all the parts and their dimensions, so it was much easier to design the Bistella 500 engine only by using Jawa engine parts.

Second reason for using the Jawa “Perak” was legislation. When you want to legalize a custom bike in CZ, you have to pass multiple safety inspections. And our law sets baselines for safety based on the safety standards of the year when the base motorcycle was produced. So, an older bike means a lower baseline. So I chose the oldest Jawa available in my price range.

Another issue with legalization of the bike is that CZ law restricts customization to only one major part of the bike. Meaning you have to choose if you want to rebuild the engine or frame or bodywork. If you combine them, and for example you change engine and suspension, it’s impossible to legalize the bike in CZ. So I modified only the engine, but radically. 😀 But I cannot touch brakes, frame, suspension etc. Those I have to keep stock in order to keep it legally on road.

• Why was this bike built?

I have built it just for the pleasure of building. I wanted to find out where the limits of my ability stand. Sometimes people do things, even when there is no logic or practical reason behind it. Like playing football, drawing pictures, or playing music. There is no point in doing such activities but still they manage to be global phenomena. I don’t have talent for sports or art, but I can build engines, so I build them. That’s my domain of art. I can’t help myself. Can’t wait to be finished with Bistella because I have another engine already seizing my mind.

• What was the design concept and what influenced the build?

I tried to avoid following any known concept. That was the point behind the Bistella. But I need to admit that I borrowed engine layout from Naga Lima by Psycho Engine. That concept they came up with is just genius. Perfect for a homemade engine, because it allows you to use a huge amount of stock components.

• What custom work was done to the bike?

Whole engine including exhaust and intake manifolds, all electronics. Wooden ignition panel with RPM gauge and pocket watch. Custom-made speedometer. Nine-layer paint job with gold leaf finish.

• Does the bike have a nickname?

Official name is “Bistella 500,” but sometimes I call it all kind of names especially when it breaks. My favorite are “hog, devil’s fork, rattlesnake, piece of shit, or bucket.” But this is mostly because I have spent so much time with it, so I got a little bit of tired of the official name “Bistella”.

• Can you tell us what it’s like to ride this bike?

It’s a life-threatening experience. It accelerates faster than it brakes. But it’s fun. Bike is really agile thanks to the relatively small dimensions of the donor bike. The donor was designed for speeds around 80kmh. So it’s short and has a relatively sharp steering angle. Like Buell bikes compared to H-D. So you have to pay attention all the time, otherwise you could end up in a ditch after opening throttle.

• Was there anything done during this build that you are particularly proud of?

Not giving up, not paying attention to the good advice of people around me, who were telling me that my build didn’t make any sense. Also I had to visit multiple CNC manufacturing companies before I found one who would manufacture parts for my engine. I have heard that I’m nuts so many times that I don’t even listen. I just calmly moved to another meeting, assuring myself that there is one “princess” out there who will accept my offer. And I found a company where a lot of bikers worked, and they were excited about the idea and made parts for me — that was a little miracle.